Looking to gain additional insight into both the causes and perpetrators of elk mortality in Idaho’s panhandle region, state biologists look very closely at the clues left at each site.

For the past two years, biologists with the Idaho Fish and Game Panhandle Region have been monitoring the activity of elk through the use of 172 GPS radio-collars. Each of these collars were placed on 6-month old elk calves in the Coer D’Alene and St. Joe River drainages to give researchers more data about elk mortality in the region.

The GPS collars are toted around by the study animals until something goes wrong. After a collar has been idle for a number of hours, they send an automatic email for biologists containing the location of the collar.

These notifications immediately mobilize biologists who aim to be on the site within 24-48 hours. Each email that comes in from an idle collar, typically indicates a dead elk, prompting researchers to get on site as quickly as possible to assess the death and figure out what may have caused it.

“Once we get to the location and find the elk, we take a crime scene approach. We conduct a careful search around the carcass looking for predator tracks, hair, drag trails in the dirt or snow, broken branches that indicate a chase, and blood on vegetation or the ground,” said Laura Wolf, IDFG regional biologist.

While the signal beaming from the collar certainly makes the job of responding biologists slightly easier, the real work begins when the partially consumed carcass is found. Acting much the same as police detectives, biologists then would create a perimeter around the animal and search for clues.

According to biologists, predators such as wolves and mountain lions each leave their own calling card for those willing to do the work in determining a guilty party. When it comes to wolves, a chase is usually involved, sometimes over rather far distances. These predators will bite hindquarters, flanks, and necks of their prey until they are able to get it on the ground. The crime scene is often a scattered one, as wolves will not leave much behind when they are finished. As a pack animal, many of these scenes will involve scattered pieces of the carcass in a fairly large area as members of the pack take their own meat to consume.

Mountain lions, on the other hand, are calculated killers. These ambush predators use their stalking skills and quickly dispatch their prey with little chase. In these cases, the attack and kill sites are often very closely situated and lions will often drag their prey to a more secluded area, leaving drag marks in and around the kill site.

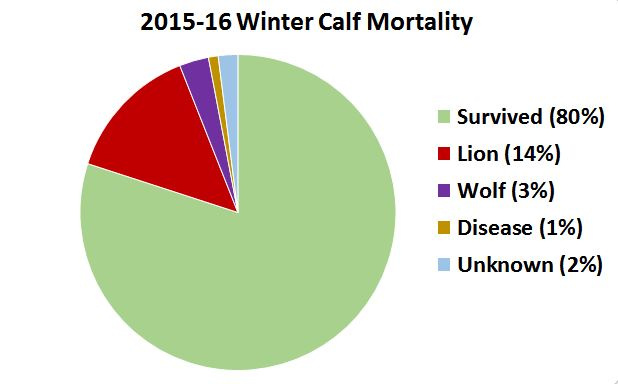

When compiling the data from the two-year study, researchers were easily able to pinpoint the direct causes of elk mortality in the area, at least among the studied population. During the winters of 2015 and 2016, 80 percent of the elk calves survived from January to June. The remaining 20 percent was consumed by mountain lions (14%), wolves (3%), disease (1%) and unknown causes (2%).

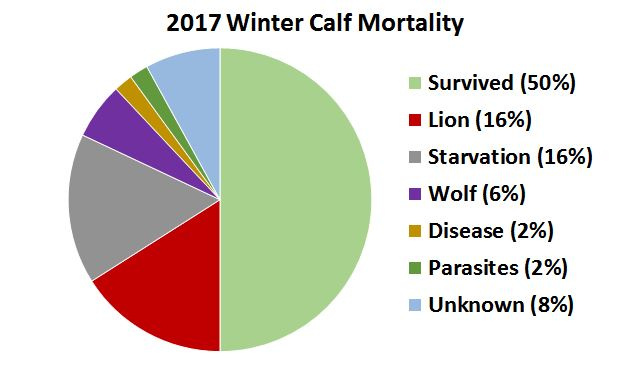

Last year’s cold and precipitous winter was much harder on elk calves, with only a 50 percent rate of survival. Despite the much higher mortality rate, predation rates remained relatively constant; 16% were killed by mountain lions and 6% were killed by wolves. Starvation (16%), heavy parasite loads (2%), and disease (2%) accounted for the difference in survival rates among the winters.

In addition to the data compiled during this study, biologists now are compiling additional data such as cow survival rates, calf:cow ratios, and the percent of spikes in the harvest. The data will be utilized when making future decisions regarding the scientific management of these animals in years to come.