Managing wildlife and wildlife habitats throughout an area known as the Wek’èezhii in Canada’s Northwest Territories, the Wek’èezhii Renewable Resources Board (WRRB) has voiced their recommendation of halting the harvest of the Bathurst Caribou.

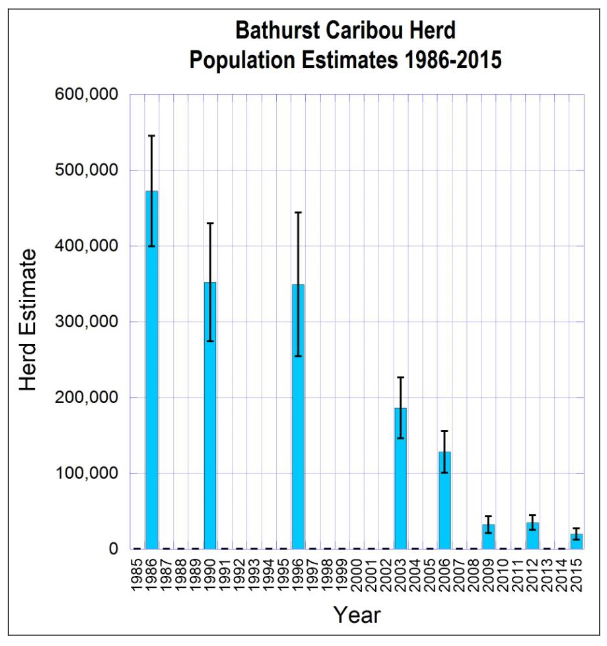

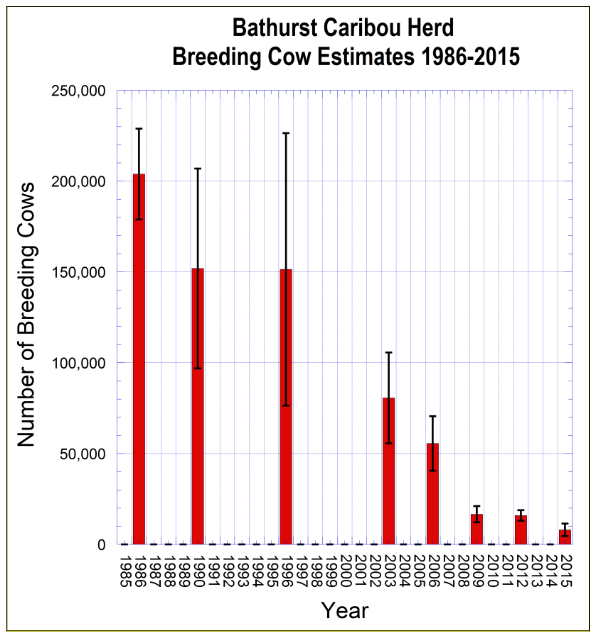

Named after Bathhurst Inlet, the herd’s fertile calving grounds, the Bathurst herd of barren-ground caribou’s population has been in sharp decline over the past thirty years. Overall, the population of the Bathurst caribou has declined by as much as 90 percent since 2003, according to population estimates.

“The trends from these surveys suggest that both herds are declining at an alarming rate,” Michael Miltenberger, the N.W.T’s environment and natural resource minister, said in a 2014 news release.

A Tłı̨chǫ Traditional Knowledge Study indicated that mining and development, disrespectful behavior and outfitters camps as the top three factors affecting the health of the Bathurst caribou herd, reporting noticable changes to caribou migration routes and abnormal occurrences in caribou physiology and health.

In its most recent Report on Proposed Management Actions for Bathurst Caribou in Wek’èezhii, the WRRB proposed the closure of all harvesting of the Bathurst caribou herd, wolf management actions, and ongoing biological monitoring.

In 2010, all resident, commercial and outfitted harvesting of the caribou was suspended other than a limited bull-only Aboriginal harvest of 300 animals, which was revised to just 15 animals in 2014-2015. The recent population estimates paired with a sharp decline in breeding females and corresponding poor breeding rates have led the WRRB to recommend a zero harvest of the Bathurst herd extending into 2019.

The board has also received strong interest from both Aboriginal governments and communities supporting the harvest of wolves to aid the recovery of the Bathurst herd. While wolf populations have declined in tandem with the caribou populations, the proposal outlines the belief that approximately 55 percent of the wolf population in the region should be removed over a four year period to increase ungulate survival rates.

Northwest Territories’ Environment and Natural Resources has consulted closely with biologists and managers of the Alaska Department of Fish and Game, where a 30 percent removal of wolves is considered as a sustainable harvest.

A second part of the proposal is expected from the WRRB in August of this year and will deal with additional predator management actions, biological and environmental monitoring, and cumulative effects.